My Dad vs TomTom Sat Nav

Christmas day 2024. My parents arrived an hour late and were clearly very flustered.

In an exasperated manner they explained they had been around the one-way system four times as the Sat Nav was directing them incorrectly. They were using Google Maps as they ‘could not find the address’ in their TomTom device. To be honest, I found both scenarios implausible because, in my experience, issues with technology tend to lie with the user, not the technology. However, in this case they did have a point.

They were using Google Maps as a fallback, as they could not find an accurate destination address in TomTom. I find Google Maps to be very accurate, so I think this was a case of my father not being in the right lane to exit the one-way systems. Of course, my dad will never admit to that.

When they had calmed down, my dad asked me to locate the address in TomTom and promptly handed me the device.

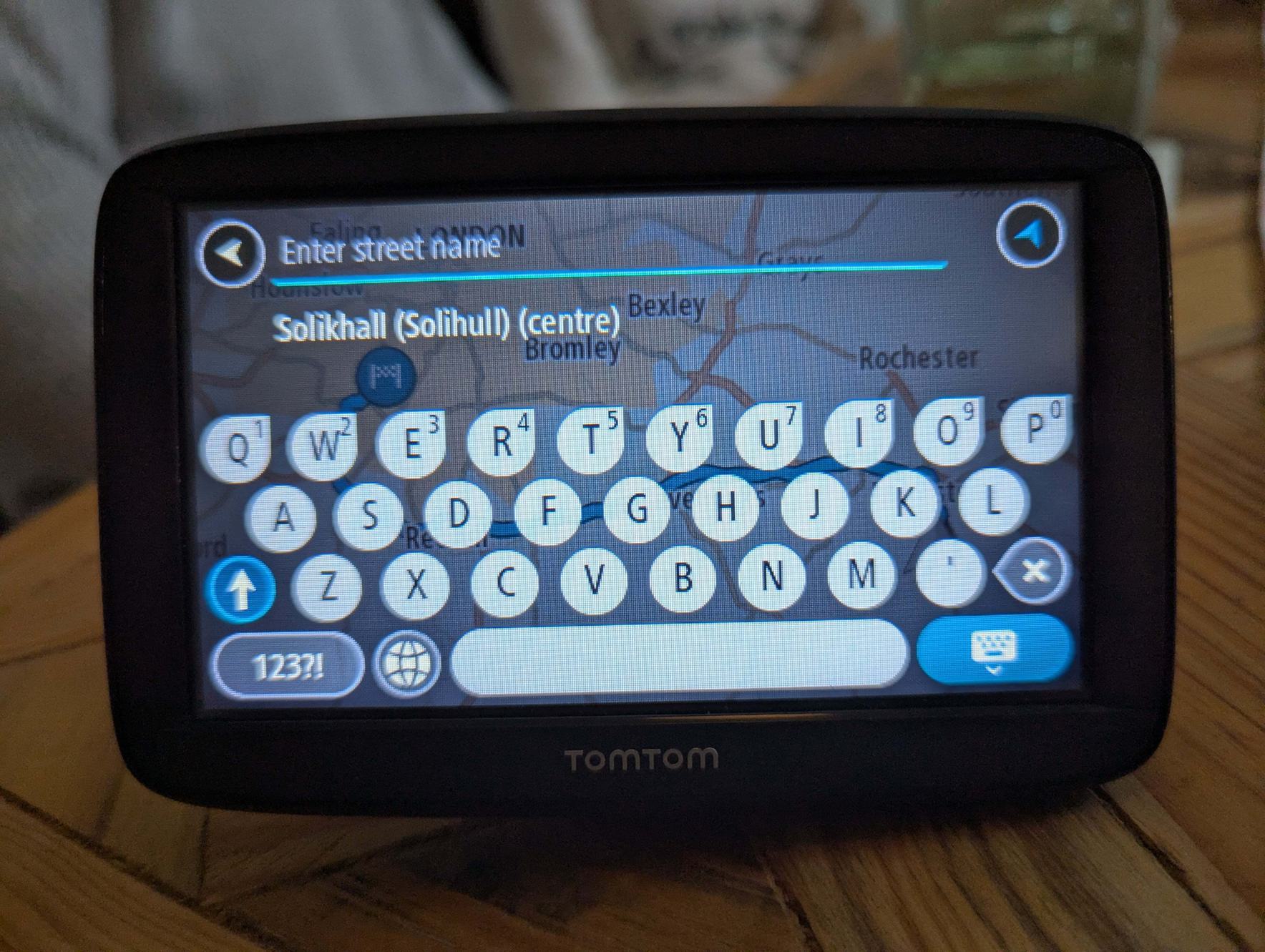

After the TomTom device booted up, I followed the instructions and Et voilà, I located the destination address. First attempt. No problems. It was the second time that day my dad had the same exasperated look on his face as he asked, ‘What did I do?’

‘Followed the instructions’ I explained.

‘What instructions?’ he asked.

It is this last question that is most telling. Walking him through the steps I took he admitted that he did not see the instructions which were added as placeholder text in the search field.

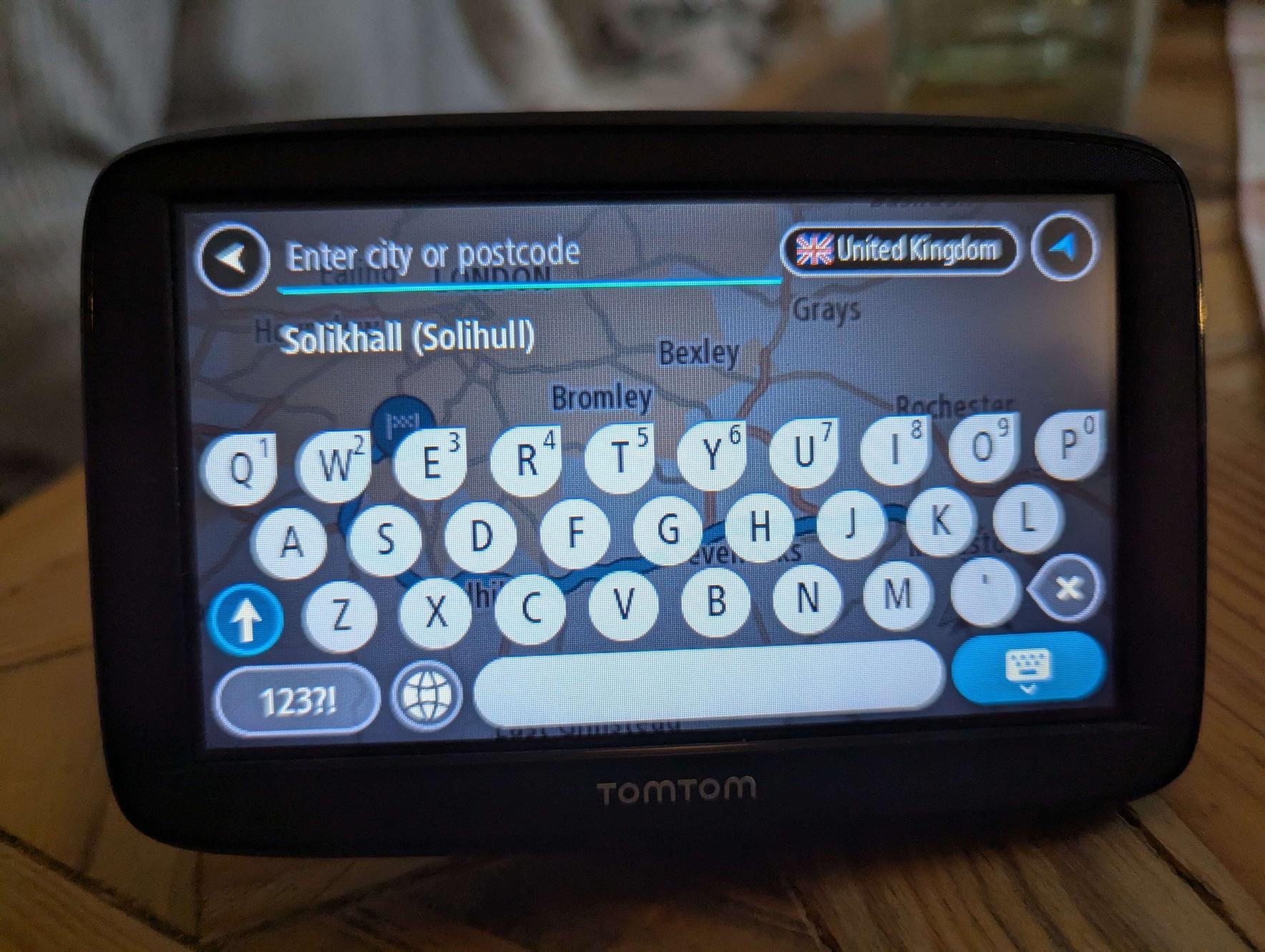

Like most other users, my father relied on learnt behaviour from his experience using other design systems. Jakob’s Law is a really important concept of UX design and is a principle that should not be ignored. Basically, inherited knowledge sets expectations on how a design should work, so my dad ignored the instructions TomTom was providing and immediately entered the postcode, not the street name…

Once he added the street name, he should have then followed it with the city or postcode…

My parents are in their late 70s. Their eyesight is okay, but not perfect — which is to be expected. The pale blue placeholder text (which disappears when you click into the field) on a busy background, surrounded by a lot of other distracting interactive elements meant my father was essentially blinded to the most important part: the instructions.

Even if I found it easy to use, both my parents did not.

The instruction text lacks contrast and features low in the visual hierarchy. The back button, keypad, country select menu and dynamically updating list of places demand more attention.

This is why a poor User Interface (UI) leads to a poor User eXperience (UX) that results in bad accessibility. A lack of text contrast is a common failure for most digital environments and it is something I see often when auditing websites, yet you do not need to have a severe disability for this to hinder a user’s ability to complete a task.

Accessibility is not solely about ‘extreme or edge cases’. Making accessible products is about total digital inclusion.

My father was trying to get to his granddaughter’s house on Christmas Day in time for Christmas dinner and he was blighted by poor text contrast.

The TomTom User Interface could be easily remodelled with a few simple changes so it encompasses all users’ needs. In fairness, this is an old model, so perhaps changes for improved accessibility have already been made. Hilariously, my parents got lost going home so they do need to take some responsibility.

At this juncture, it would be remiss of me if I did not say ‘Accessibility is for life, not just for Christmas’. One accessibility audit is never enough. It is just a shame TomTom doesn’t know this as they nearly ruined our Christmas.

References

Article by Simon Leadbetter

The Accessibility Guy at Kindera